A PROSECUTOR'S PERSPECTIVE

MARINE DEFENDER: Richard Udell

US Department of Justice, Environmental Crimes Section

By Micah Fink

"Deliberate pollution from ships is a very serious problem,” says Richard Udell, a veteran prosecutor in the US Department of Justice’s Environmental Crime Section. “It's a virtual epidemic.”

Udell should know. He's been the lead attorney on dozens of cases involving the intentional dumping of oil from ships and has developed a deep understanding of both the economics and the artful dodging carried out by what he calls "outlaw" companies willing to pollute the marine environment and violate both US and international laws in an attempt to save money.

“What we learned early on was that it was commonplace for ships to dump their waste oil in the ocean,” says Udell, who has been fighting marine oil pollution for nearly three decades. “It's not a mistake, it's not an accident. It's deliberate. These are cookie-cutter cases. They’re all pretty much the same. It’s the same waste, it’s the same pollution prevention equipment, the same records. It’s hard to think of any other industry where there’s an environmental crime that’s so prevalent, so common."

Udell should know. He's been the lead attorney on dozens of cases involving the intentional dumping of oil from ships and has developed a deep understanding of both the economics and the artful dodging carried out by what he calls "outlaw" companies willing to pollute the marine environment and violate both US and international laws in an attempt to save money.

“What we learned early on was that it was commonplace for ships to dump their waste oil in the ocean,” says Udell, who has been fighting marine oil pollution for nearly three decades. “It's not a mistake, it's not an accident. It's deliberate. These are cookie-cutter cases. They’re all pretty much the same. It’s the same waste, it’s the same pollution prevention equipment, the same records. It’s hard to think of any other industry where there’s an environmental crime that’s so prevalent, so common."

A Harmful Quantity of Oil

Udell first began working as a prosecutor with the Department of Justice’s Environmental Crime Division in 1990, a year after the Exxon-Valdez oil tanker ran aground in Alaska's Prince William Sound, spilling 11 million gallons of crude oil into a nearly pristine ecosystem. It was the largest oil spill in the United States up to the time. Graphic images of oiled birds and oil washing up on Alaska's virgin shores dramatized the devastating impact of oil on marine life and galvanized public concern. The Exxon-Valdez spill also inspired Congress to strengthen the laws relating to marine oil pollution by passing The Oil Pollution Act of 1990.

This new law increased the penalties and greatly expanded the government's ability to prosecute the companies and individuals responsible for marine oil pollution. "It made it a crime to knowingly discharge a harmful quantity of oil into our navigable waters, our contiguous zone, and our exclusive economic zone, which ultimately means 200 miles from shore," says Udell. "And it has been a powerful tool for prosecutors and law enforcement."

"What's a harmful quantity?" Udell asks rhetorically. “If you can see it. If you can see a sheen or slick on the water or on the adjoining shorelines, according to the legal terminology, it’s a harmful quantity.”

Government prosecutors also had the ability to provide financial awards to whistleblowers who reported illegal activity on ships. This "secret weapon," as it's known by lawyers who defend corporate interests, was created by Congress when it passed the Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships (APPS) in 1980 to write the terms of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) into US law. APPS included a whistleblower provision which stipulates that mariners can receive up to one half of the criminal fine when they report illegal acts which lead to a conviction.

Armed with these legal tools, the Justice Department began to focus on marine oil pollution, and to their amazement they found that illegal dumping was not only common place -- it was also difficult to deter.

“When we began working on these cases,” Udell explains, “we thought once we had prosecuted several high-profile players in the Maritime industry that word would get out and we would move onto other subjects. But there has been no let up. Year after year we continue to get criminal cases referred to us by the Coast Guard, and we know it's just a small fraction of the crime that's occurring."

This new law increased the penalties and greatly expanded the government's ability to prosecute the companies and individuals responsible for marine oil pollution. "It made it a crime to knowingly discharge a harmful quantity of oil into our navigable waters, our contiguous zone, and our exclusive economic zone, which ultimately means 200 miles from shore," says Udell. "And it has been a powerful tool for prosecutors and law enforcement."

"What's a harmful quantity?" Udell asks rhetorically. “If you can see it. If you can see a sheen or slick on the water or on the adjoining shorelines, according to the legal terminology, it’s a harmful quantity.”

Government prosecutors also had the ability to provide financial awards to whistleblowers who reported illegal activity on ships. This "secret weapon," as it's known by lawyers who defend corporate interests, was created by Congress when it passed the Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships (APPS) in 1980 to write the terms of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) into US law. APPS included a whistleblower provision which stipulates that mariners can receive up to one half of the criminal fine when they report illegal acts which lead to a conviction.

Armed with these legal tools, the Justice Department began to focus on marine oil pollution, and to their amazement they found that illegal dumping was not only common place -- it was also difficult to deter.

“When we began working on these cases,” Udell explains, “we thought once we had prosecuted several high-profile players in the Maritime industry that word would get out and we would move onto other subjects. But there has been no let up. Year after year we continue to get criminal cases referred to us by the Coast Guard, and we know it's just a small fraction of the crime that's occurring."

Enforcing MarPOL

MARPOL is an international treaty, signed by the US and 99% of the world's seafaring nations, that set the legal foundations for the global battle against intentional dumping of oil and other ship based pollution. "This is a treaty that is successful in terms of the number of countries that signed on," says Udell. "But in terms of enforcement and the level of violation, much less successful."

MARPOL's goal, says Udell, reading from a copy of the treaty that he keeps on his desk, “is the complete elimination of intentional pollution of marine environment by oil and other harmful substances, and the minimization of accidental discharge of such substances.”

Virtually all modern shipping uses oil in their engine rooms, and in the course of ordinary operations they produce large amounts of oily waste and sludge that collects in the ship's bilge. Before MARPOL was passed in 1973, most ships simply dumped their oily waste directly into the ocean. Conscious of the damage this dumping was doing to the ocean environment, MARPOL set strict rules for the treatment and tracking of oily water, sludge, and other pollutants on ships.

“MARPOL was written because the oceans are precious,” Udell explains. "On ships there is often a culture that not anything I can possibly do would injure the ocean, but we know that it does. The ocean water may seem vast, but it’s not limitless."

MARPOL's goal, says Udell, reading from a copy of the treaty that he keeps on his desk, “is the complete elimination of intentional pollution of marine environment by oil and other harmful substances, and the minimization of accidental discharge of such substances.”

Virtually all modern shipping uses oil in their engine rooms, and in the course of ordinary operations they produce large amounts of oily waste and sludge that collects in the ship's bilge. Before MARPOL was passed in 1973, most ships simply dumped their oily waste directly into the ocean. Conscious of the damage this dumping was doing to the ocean environment, MARPOL set strict rules for the treatment and tracking of oily water, sludge, and other pollutants on ships.

“MARPOL was written because the oceans are precious,” Udell explains. "On ships there is often a culture that not anything I can possibly do would injure the ocean, but we know that it does. The ocean water may seem vast, but it’s not limitless."

The oily water separator

There are a few “critical regulations” in MARPOL, Udell explains, and in the United States the Coast Guard is tasked with enforcing them in American ports and waters.

One key requirement is that all ocean-going vessels over 400 tons must carry an oil-water separator, which is a pollution prevention device designed to process oil-contaminated waste water.

"The oily water separator also has to have an oil content monitor, which measures the concentration of oil in the water," says Udell. This is important because MARPOL, and US law, prohibits the release of water that has a concentration of oil present higher than 15 parts per million.

Only waste water contains 15 parts of oil per million, or less, can legally be discharged overboard. Waste water containing higher concentrations of oil must remain on the ship and must be either incinerated on board or off loaded at port. "The idea is that the oil stays on the ship," says Udell. "If you are discharging waste water and it's not through an oily water separator, or the oil content is above 15 part per million, you are violating MARPOL.”

“This limit was established in part because oil becomes visible around 100 parts per million,” Udell explains. “If you can see oil in the water, if you can see an oil slick, you know that it's a violation of MARPOL. And it's a violation no matter where it occurs."

One key requirement is that all ocean-going vessels over 400 tons must carry an oil-water separator, which is a pollution prevention device designed to process oil-contaminated waste water.

"The oily water separator also has to have an oil content monitor, which measures the concentration of oil in the water," says Udell. This is important because MARPOL, and US law, prohibits the release of water that has a concentration of oil present higher than 15 parts per million.

Only waste water contains 15 parts of oil per million, or less, can legally be discharged overboard. Waste water containing higher concentrations of oil must remain on the ship and must be either incinerated on board or off loaded at port. "The idea is that the oil stays on the ship," says Udell. "If you are discharging waste water and it's not through an oily water separator, or the oil content is above 15 part per million, you are violating MARPOL.”

“This limit was established in part because oil becomes visible around 100 parts per million,” Udell explains. “If you can see oil in the water, if you can see an oil slick, you know that it's a violation of MARPOL. And it's a violation no matter where it occurs."

MAGIC PIPES

One of the most frequent ways that companies break the law is by using what has come to be known in the industry as a "magic pipe," says Udell, "because it makes the oil magically disappear."

Magic pipes can take many forms and Udell keeps a number of them in his office as examples of the devious creativity of human invention when driven by greed. One was found hidden in the boiler blowdown. Another was secreted under the ship's deck plates and used to discharge oily water through the ship's clean water system. While their shapes may vary, they were all created for the same purpose: to violate MARPOL by sending sludge and oily waste water overboard in the ocean.

“Over the years we have learned a lot about how ships work and how many of these crimes can be detected in port just by a simple examination,” says Udell. “For example, the Coast Guard will dismantle the last pipe going overboard. That's a pipe that shouldn't have any visible oil in it because the legal standard is 15 parts per million and you can't see 15 parts per million. And yet, we have pipes that are just filled with black oil, a million parts per million. And in just five minutes a look at the overboard pipe can tell us is this ship dumping.”

Magic pipes can take many forms and Udell keeps a number of them in his office as examples of the devious creativity of human invention when driven by greed. One was found hidden in the boiler blowdown. Another was secreted under the ship's deck plates and used to discharge oily water through the ship's clean water system. While their shapes may vary, they were all created for the same purpose: to violate MARPOL by sending sludge and oily waste water overboard in the ocean.

“Over the years we have learned a lot about how ships work and how many of these crimes can be detected in port just by a simple examination,” says Udell. “For example, the Coast Guard will dismantle the last pipe going overboard. That's a pipe that shouldn't have any visible oil in it because the legal standard is 15 parts per million and you can't see 15 parts per million. And yet, we have pipes that are just filled with black oil, a million parts per million. And in just five minutes a look at the overboard pipe can tell us is this ship dumping.”

Lying in Port?

“There's one more critical element to the MARPOL regulations,” says Udell. “The requirement that internal transfers and overboard discharges are recorded in what's known as an oil record book. An oil record book is the bible, or whatever holy book you prefer, in which all discharges, and all transfers of oil on or off the ship, are recorded.”

“Nobody is writing down we're dumping overboard today,” Udell explains, which makes figuring out that a crime has taken place into a puzzle that can only be solved by careful detective work.

“Instead they're typically having omissions or other falsifications," says Udell. "For example, claiming that the pollution prevention equipment is being used when in fact it wasn't."

“In the United States, our approach to jurisdiction has been to focus on the record that the ship has when it comes to port,” explains Udell. “When a ship comes to port and its log book has been falsified, it is literally ‘lying in port’ -- no pun intended. You're lying to the government about something that we consider quite important. Does your oily water separator work? What happened to your waste? And that's true for an oil record book or a garbage record book. Both are required log books which are regularly inspected by the US Coast Guard.”

“Just seeing that there is pollution in the water, pollution behind a ship, doesn't necessarily make it a crime in the United States,” says Udell. "We're looking to find out was it a knowing violation. That means legally is it deliberate, on purpose, not an accident or a mistake. In order for it to be a crime it has to be on purpose, because that's what makes it a felony.”

"Making a material false statement is of the most frequently prosecuted crimes," Udell explains. “Material, in this case, just means it's important."

“Falsifying an oil record book or other ship record is a serious crime in the United States,” says Udell. "Depending under which law it is prosecuted it can be a five-year felony or even up to a twenty-year felony. For a corporation, the fine is up to $500,000 dollars per crime. For an individual it's up to $200,000.”

“Nobody is writing down we're dumping overboard today,” Udell explains, which makes figuring out that a crime has taken place into a puzzle that can only be solved by careful detective work.

“Instead they're typically having omissions or other falsifications," says Udell. "For example, claiming that the pollution prevention equipment is being used when in fact it wasn't."

“In the United States, our approach to jurisdiction has been to focus on the record that the ship has when it comes to port,” explains Udell. “When a ship comes to port and its log book has been falsified, it is literally ‘lying in port’ -- no pun intended. You're lying to the government about something that we consider quite important. Does your oily water separator work? What happened to your waste? And that's true for an oil record book or a garbage record book. Both are required log books which are regularly inspected by the US Coast Guard.”

“Just seeing that there is pollution in the water, pollution behind a ship, doesn't necessarily make it a crime in the United States,” says Udell. "We're looking to find out was it a knowing violation. That means legally is it deliberate, on purpose, not an accident or a mistake. In order for it to be a crime it has to be on purpose, because that's what makes it a felony.”

"Making a material false statement is of the most frequently prosecuted crimes," Udell explains. “Material, in this case, just means it's important."

“Falsifying an oil record book or other ship record is a serious crime in the United States,” says Udell. "Depending under which law it is prosecuted it can be a five-year felony or even up to a twenty-year felony. For a corporation, the fine is up to $500,000 dollars per crime. For an individual it's up to $200,000.”

Why do they do it?

“In environmental crimes cases we don't have to prove motive,” says Udell. “We don't have to prove why somebody did it, but it is what every juror and every judge wants to know. In every case I ask the witnesses, ‘Why would you do this? Why would you risk going to jail? Why would you risk your livelihood to commit this crime?'"

There are different answers, Udell says, depending on the mariner’s role on the ship.

“At the lowest level of a ship are the oilers, the wipers, the motor men,” says Udell. “These are people who may be paid $10,000-$20,000 as an annual salary and work seven days a week, 12-hours a day. And in the economy where these foreign crew come from that's still considered a good salary. Often the answer that they will give you is I work in a military chain of command. The boss tells me to do it, I have to do it. If I don't, I'll be written up, I'll be blacklisted, I'll lose my job.”

“Higher up in the command there's certainly an awareness that they're saving the company money,” Udell says. “Occasionally we develop evidence that somebody on land told somebody onboard this is what we want you to do. But often it's more subtle pressure. I remember asking a chief engineer, ‘Why did you do it?’ And he said, ‘You know, I tried to get this electric screwdriver that I really needed for my engine room, and the company didn't want to pay for that, so I knew that they wouldn't want to pay to offload the waste in port’.”

“Everybody knows what the law is," says Udell. "Every mariner has a license. Every shipping company knows what the rules are, but a shipping company that doesn't plan to take out the trash, that doesn't plan for the cost of their waste, is an outlaw. They know they're not supposed to do it, and the only reason they're doing it is to save money.”

“Now, I want to be clear about one thing,” adds Udell. “We're interested not in prosecuting every person on a ship who might have been told to commit a crime. We recognize that there's a chain of command. When we investigate and prosecute a company we're looking to find out who are the most responsible people? Who is at the top of that chain of command that knows about it and is making it happen? Who is really responsible?”

There are different answers, Udell says, depending on the mariner’s role on the ship.

“At the lowest level of a ship are the oilers, the wipers, the motor men,” says Udell. “These are people who may be paid $10,000-$20,000 as an annual salary and work seven days a week, 12-hours a day. And in the economy where these foreign crew come from that's still considered a good salary. Often the answer that they will give you is I work in a military chain of command. The boss tells me to do it, I have to do it. If I don't, I'll be written up, I'll be blacklisted, I'll lose my job.”

“Higher up in the command there's certainly an awareness that they're saving the company money,” Udell says. “Occasionally we develop evidence that somebody on land told somebody onboard this is what we want you to do. But often it's more subtle pressure. I remember asking a chief engineer, ‘Why did you do it?’ And he said, ‘You know, I tried to get this electric screwdriver that I really needed for my engine room, and the company didn't want to pay for that, so I knew that they wouldn't want to pay to offload the waste in port’.”

“Everybody knows what the law is," says Udell. "Every mariner has a license. Every shipping company knows what the rules are, but a shipping company that doesn't plan to take out the trash, that doesn't plan for the cost of their waste, is an outlaw. They know they're not supposed to do it, and the only reason they're doing it is to save money.”

“Now, I want to be clear about one thing,” adds Udell. “We're interested not in prosecuting every person on a ship who might have been told to commit a crime. We recognize that there's a chain of command. When we investigate and prosecute a company we're looking to find out who are the most responsible people? Who is at the top of that chain of command that knows about it and is making it happen? Who is really responsible?”

Whistleblower awards

“Whistle blowers play a very critical role,” Udell says in catching illegal dumping at sea.

“In the United States, the law that implements MARPOL has a whistle blower award provision,” Udell explains, which has become a very useful tool for law enforcement. “It’s a bounty provision which states that any person who provided information that leads to a conviction can get up to one half of the criminal fine.”

“A crewmember on a ship is going to witness things that happen at sea that would be very hard, sometimes impossible for the government to know about. And we've had case after case where crew members have come forward, have told the government this is what's happening on my ship, this is what's been going on. And yes, you may be risking your livelihood, you may be risking retaliation, but whistleblowers who have brought those cases to the United States have been handsomely rewarded in the past by judges overseeing those cases.”

“Typically, judges have awarded the full one-half of the criminal fine to whistleblowers,” says Udell. “We’ve had fines of $100,000, $250,000, over $400,000.”

“In the United States, the law that implements MARPOL has a whistle blower award provision,” Udell explains, which has become a very useful tool for law enforcement. “It’s a bounty provision which states that any person who provided information that leads to a conviction can get up to one half of the criminal fine.”

“A crewmember on a ship is going to witness things that happen at sea that would be very hard, sometimes impossible for the government to know about. And we've had case after case where crew members have come forward, have told the government this is what's happening on my ship, this is what's been going on. And yes, you may be risking your livelihood, you may be risking retaliation, but whistleblowers who have brought those cases to the United States have been handsomely rewarded in the past by judges overseeing those cases.”

“Typically, judges have awarded the full one-half of the criminal fine to whistleblowers,” says Udell. “We’ve had fines of $100,000, $250,000, over $400,000.”

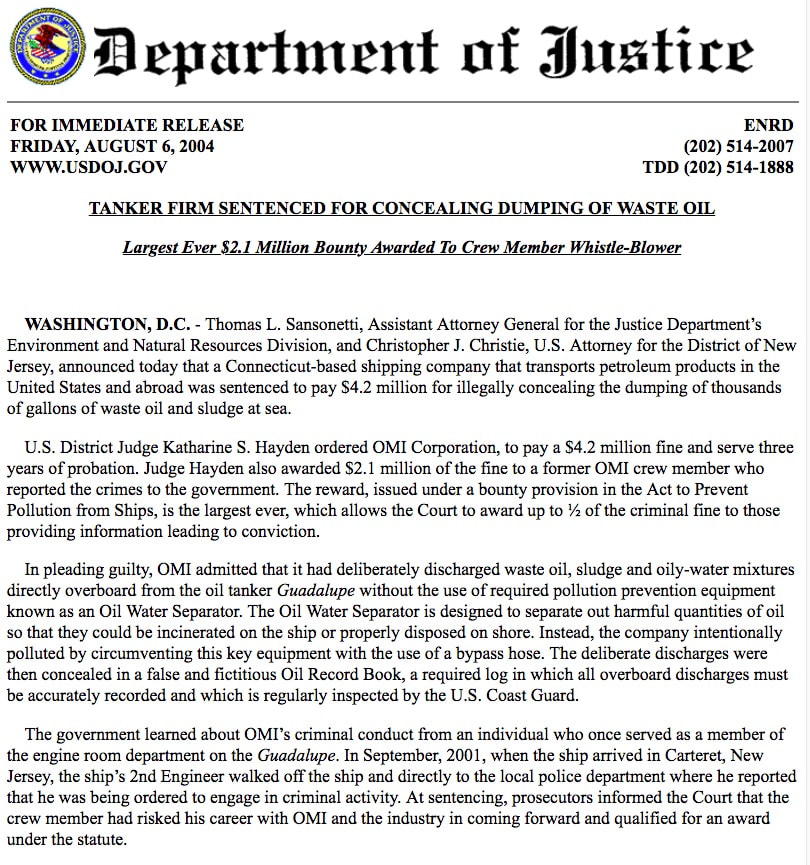

US vs OMI

“I'll give you an early example of a whistleblower case involving OMI, a US tanker company based in Stamford, Connecticut,” says Udell. “There was a Filipino member of the engine crew of the oil tanker Guadalupe. He got off the ship at the Port of Carteret in central New Jersey, and asked directions, ‘Where is the police station?’ He found the police station and he went up to the desk sergeant and said, ‘They're ordering me to dump overboard on my ship.’”

OMI ended up pleading guilty in January 2004. The company admitting to using a bypass hose to deliberately dump thousands of gallons of waste oil, sludge and oily-water mixtures directly overboard without the use of an Oil Water Separator. These discharges were then concealed by the captain and the chief engineer in a false Oil Record Book. The company paid a $4.2 million dollar fine.

The whistleblower award was half the fine. “$2.1 million dollars to one seafarer for bringing that case to the government’s attention might seem like a lot of money," says Udell. "But without his coming forward and telling the government about that crime, that company might still be dumping today. We would never have learned of that crime!”

OMI ended up pleading guilty in January 2004. The company admitting to using a bypass hose to deliberately dump thousands of gallons of waste oil, sludge and oily-water mixtures directly overboard without the use of an Oil Water Separator. These discharges were then concealed by the captain and the chief engineer in a false Oil Record Book. The company paid a $4.2 million dollar fine.

The whistleblower award was half the fine. “$2.1 million dollars to one seafarer for bringing that case to the government’s attention might seem like a lot of money," says Udell. "But without his coming forward and telling the government about that crime, that company might still be dumping today. We would never have learned of that crime!”

US vs Overseas ship holding group

"Another case that our office prosecuted was against Overseas Ship Holding Group, know as OSG," says Udell.

"It's a US-based company that operates tankers, but all the ships are flagged in foreign countries and the crew members are primarily from other countries."

The OSG case began when Transport Canada boarded a ship called the Uranus in Canada. "The Canadians compared the oil record book to a sounding log book, which records how much liquid is in the tanks," says Udell. "And the two documents told very different stories. So Canada suspected that this ship was dumping, and they were right."

The case was referred to the US Coast Guard, which began an investigation. "One ship led to another ship, to another ship," says Udell. "We learned that the crew members platooned around from ship to ship, so while interviewing a crew member on one ship we asked them what other ships did you work on and did the same practice occur there? And they were the same from ship to ship. Bilge waste and in some cases sludge, virtually pure oil, was being dumped overboard and it was done deliberately and intentionally."

"It's a US-based company that operates tankers, but all the ships are flagged in foreign countries and the crew members are primarily from other countries."

The OSG case began when Transport Canada boarded a ship called the Uranus in Canada. "The Canadians compared the oil record book to a sounding log book, which records how much liquid is in the tanks," says Udell. "And the two documents told very different stories. So Canada suspected that this ship was dumping, and they were right."

The case was referred to the US Coast Guard, which began an investigation. "One ship led to another ship, to another ship," says Udell. "We learned that the crew members platooned around from ship to ship, so while interviewing a crew member on one ship we asked them what other ships did you work on and did the same practice occur there? And they were the same from ship to ship. Bilge waste and in some cases sludge, virtually pure oil, was being dumped overboard and it was done deliberately and intentionally."

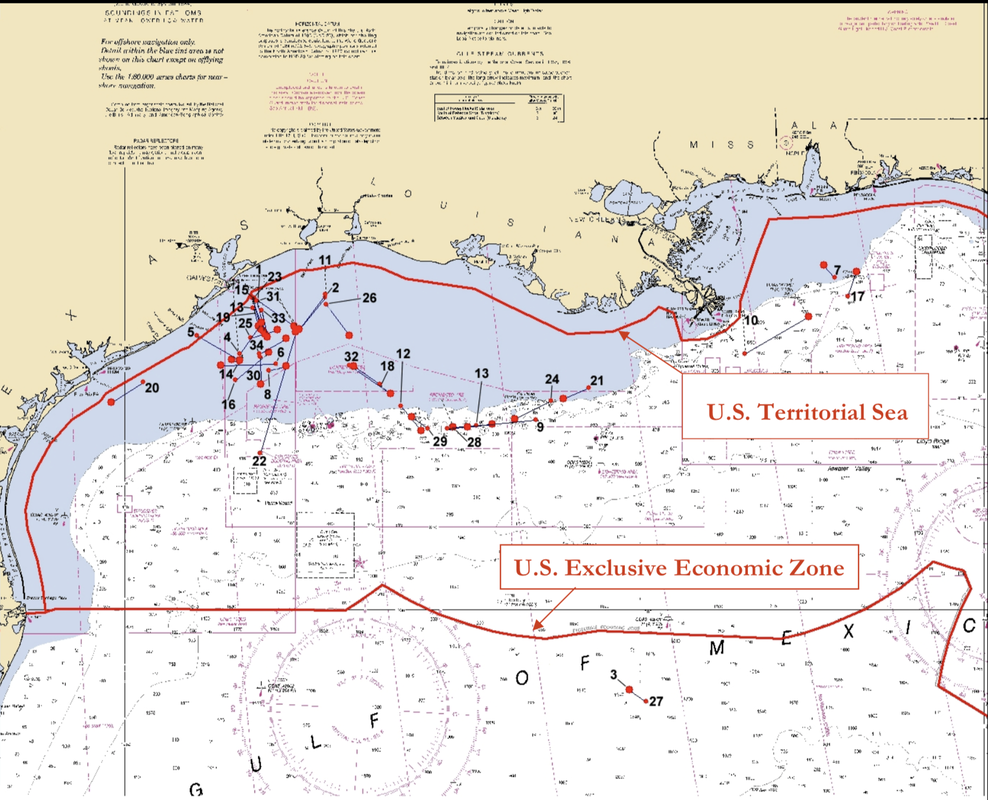

"Some of the dumping was close to land," recalls Udell. "Off the coast of Maine, near Mount Desert Island National Park, off the Texas coast, and in the Gulf of Mexico." Studying the oil records books of the Pacific Ruby, for example, US investigators were able to map out at least 29 instances where the OSG-owned ship dumped oily waste overboard into the Gulf of Mexico, along the coasts of Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama.

"Once the investigation began we interviewed crew members on the ship and we learned that some of the crew members were being forced to do it against their will," recalls Udell.

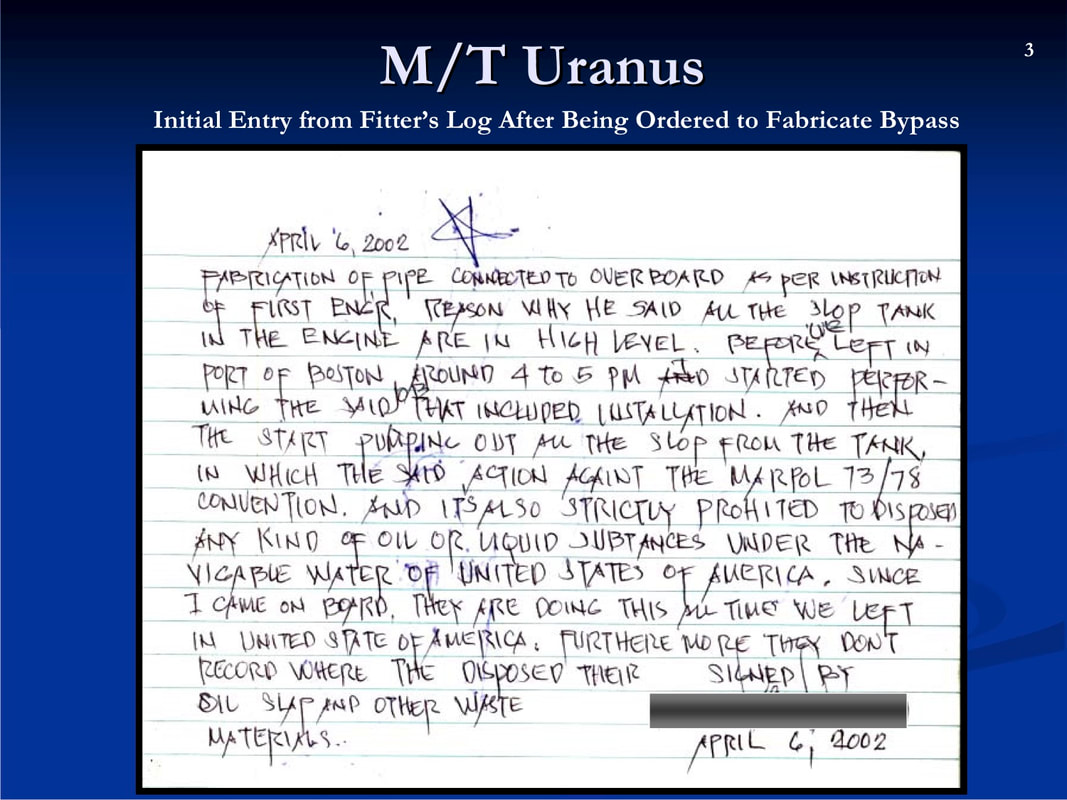

"One of those crew members came forward and he had tucked underneath his arm a little black notebook," says Udell. "He was the fitter of the ship and he was told to make a bypass pipe or he would lose his job. At first he refused, then he finally did make it. He was so angry with having to make the pipe that he created a little black book and he recorded every time that they dumped overboard. His initial note, the first entry in the book, is so meaningful because he says, “I know it’s against the law but we’re doing it all the time.”

“Fabrication of pipe connected to overboard as per instruction of First Engineer," the fitter wrote in his journal on April 6, 2002.

The First Engineer ordered him to build the pipe, he wrote, because "all the slop tank in the engine are on high level.”

The fitter then documented each time the pipe was used to discharge oil overboard.

“Before we left Port of Boston around four to five p.m., I started performing the job that included installation. And then start pumping out of all the slop from the tank, in which the said action is against MARPOL 73/78 Convention. And it’s also strictly prohibited to dispose any kind of oil or liquid substance under the navigable waters of the United States of America. Since I came on board they are doing this all time we left in the United States of America. Furthermore they don’t record where they dispose of their oil slop and other waste materials.”

These notes, supported by other whistleblower accounts, would help to build a water tight case against the company, and show that it was involved in an intentional pattern of illegal dumping in violation of MARPOL and US laws.

Once the case was tried, and OSG pled guilty, the US government lawyers wrote a brief arguing that the whistleblowers should receive handsome awards.

They explained their reasoning in this way:

"Because the pollution takes place in the middle of the ocean and usually at night, the only people likely to know about the conduct and the falsification of ship records used in port are the employees in the engine room."

Each year, thousands of seafarers participate in or are aware of illegal conduct aboard their vessels. A tiny minority chooses to take active measure to stop the wrongdoing and bear witness. The government’s success in identifying the activity and obtaining sufficient evidence to support investigations and prosecutions is dependent on the willingness of lower level crew members to step forward."

The decision to step forward, however, must be weighed against the likelihood that the cooperating crew member will forever be barred from working in the marine shipping industry and may be subject to physical harm and abuse. In fact, several crew members in this case perceived that their employment was threatened and/or their physical safety was in jeopardy as a direct result of blowing the whistle on crime.”

"A substantial monetary award both rewards the crew member for taking that risk and may provide an incentive for fellow crew members to alert inspectors and investigators of similar conduct on other ships in the future."

"For these reasons, significant whistleblower awards have become a routine practice where the facts support a reward."

"The ship's fitter who provided his notes received over $400,000 dollars as a whistleblower award from the court for cooperating with law enforcement," notes Udell.

"To have a large publicly traded company head-quartered in the US engage in this conduct was shocking," Udell recalls. "And it wasn't just an isolated event. It wasn't just one ship or two ships. We found that twelve OSG ships had illegal crimes taking place on board. And it resulted in a $37 million dollar penalty.”

The Overseas Ship Holding Group eventually pled guilty to 33 felony counts relating to deliberate vessel pollution from nine ships, and false pollution log entries in three additional ships. The company paid a record $37 million dollars penalty and total of $5.25 million dollars was paid out to whistleblowers who helped to build the case.

The First Engineer ordered him to build the pipe, he wrote, because "all the slop tank in the engine are on high level.”

The fitter then documented each time the pipe was used to discharge oil overboard.

“Before we left Port of Boston around four to five p.m., I started performing the job that included installation. And then start pumping out of all the slop from the tank, in which the said action is against MARPOL 73/78 Convention. And it’s also strictly prohibited to dispose any kind of oil or liquid substance under the navigable waters of the United States of America. Since I came on board they are doing this all time we left in the United States of America. Furthermore they don’t record where they dispose of their oil slop and other waste materials.”

These notes, supported by other whistleblower accounts, would help to build a water tight case against the company, and show that it was involved in an intentional pattern of illegal dumping in violation of MARPOL and US laws.

Once the case was tried, and OSG pled guilty, the US government lawyers wrote a brief arguing that the whistleblowers should receive handsome awards.

They explained their reasoning in this way:

"Because the pollution takes place in the middle of the ocean and usually at night, the only people likely to know about the conduct and the falsification of ship records used in port are the employees in the engine room."

Each year, thousands of seafarers participate in or are aware of illegal conduct aboard their vessels. A tiny minority chooses to take active measure to stop the wrongdoing and bear witness. The government’s success in identifying the activity and obtaining sufficient evidence to support investigations and prosecutions is dependent on the willingness of lower level crew members to step forward."

The decision to step forward, however, must be weighed against the likelihood that the cooperating crew member will forever be barred from working in the marine shipping industry and may be subject to physical harm and abuse. In fact, several crew members in this case perceived that their employment was threatened and/or their physical safety was in jeopardy as a direct result of blowing the whistle on crime.”

"A substantial monetary award both rewards the crew member for taking that risk and may provide an incentive for fellow crew members to alert inspectors and investigators of similar conduct on other ships in the future."

"For these reasons, significant whistleblower awards have become a routine practice where the facts support a reward."

"The ship's fitter who provided his notes received over $400,000 dollars as a whistleblower award from the court for cooperating with law enforcement," notes Udell.

"To have a large publicly traded company head-quartered in the US engage in this conduct was shocking," Udell recalls. "And it wasn't just an isolated event. It wasn't just one ship or two ships. We found that twelve OSG ships had illegal crimes taking place on board. And it resulted in a $37 million dollar penalty.”

The Overseas Ship Holding Group eventually pled guilty to 33 felony counts relating to deliberate vessel pollution from nine ships, and false pollution log entries in three additional ships. The company paid a record $37 million dollars penalty and total of $5.25 million dollars was paid out to whistleblowers who helped to build the case.

"One of the amazing things about the OSG case was that it occurred more than ten years after our first prosecutions, so the word was out," says Udell. "People in the maritime industry knew that this was a crime. On every ship there's a placard that's located right next to the oily water separator and the overboard valve that says dumping oil is a crime. That's a required sign to have on your ship.”

“When a ship is systematically dumping in the way that we found in the OSG case,” says Udell. “It's usually a sign of a corporate culture. A whole group of people, a whole department, had not convinced their employees to obey the law.”

"One part of what we do in criminal cases that involve the environment, we try to get some kind of corrective action," Udell explains. "In the OSG case we required a compliance plan, a new one. Not their plan, our plan. And we required that there were independent auditors looking at how they were doing and monitoring their ship. And we required that a court appointed monitor also review those audits. That's an intrusive process for an industry, but it's something that a convicted criminal deserves. And it's designed to prevent the pollution in the future.”

“I think that we made a huge impression on the company,” Udell adds. “In one of the sentencing proceedings, the corporate representative actually said ‘this has changed our company for the better, and we're sorry.’"

“When a ship is systematically dumping in the way that we found in the OSG case,” says Udell. “It's usually a sign of a corporate culture. A whole group of people, a whole department, had not convinced their employees to obey the law.”

"One part of what we do in criminal cases that involve the environment, we try to get some kind of corrective action," Udell explains. "In the OSG case we required a compliance plan, a new one. Not their plan, our plan. And we required that there were independent auditors looking at how they were doing and monitoring their ship. And we required that a court appointed monitor also review those audits. That's an intrusive process for an industry, but it's something that a convicted criminal deserves. And it's designed to prevent the pollution in the future.”

“I think that we made a huge impression on the company,” Udell adds. “In one of the sentencing proceedings, the corporate representative actually said ‘this has changed our company for the better, and we're sorry.’"

Become A Marine Defender

The US Coast Guard, following the attacks of September 11, 2001, began boarding and inspecting all foreign flag-state vessels calling on US ports. This heightened security has also substantially heightened scrutiny of vessels and ship's records and logs.

“The United States has a reputation for being the most enforcement-minded and having the strongest enforcement for MARPOL crimes,” Udell says. “And, as far as I know the United States is the only country that has a whistleblower award."

"We’re reaching out for help," says Udell. "Help us to prosecute these cases. Help us to stop this crime. Help us to protect the world’s oceans.”

“The United States has a reputation for being the most enforcement-minded and having the strongest enforcement for MARPOL crimes,” Udell says. “And, as far as I know the United States is the only country that has a whistleblower award."

"We’re reaching out for help," says Udell. "Help us to prosecute these cases. Help us to stop this crime. Help us to protect the world’s oceans.”