Red Knots and Horseshoe Crabs in Delaware Bay by Common Good Productions.

A Shore Bird Biologist's Perspective

MARINE DEFENDER: JOANNA BURGER

RUTGERS UNIVERSITY, Department of Ecology, Evolution, and natural Resources

DEFENDING THE RED KNOTS

CAPE MAY, NEW JERSEY

Dr. Joanna Burger, a specialist in shore birds, visited Cape May, New Jersey, in the Spring of 2012 with a group of bird biologist to witness a remarkable annual event. Each year, Red Knots stop along this rocky shore for a brief period to feast on eggs laid by spawning horseshoe crabs.

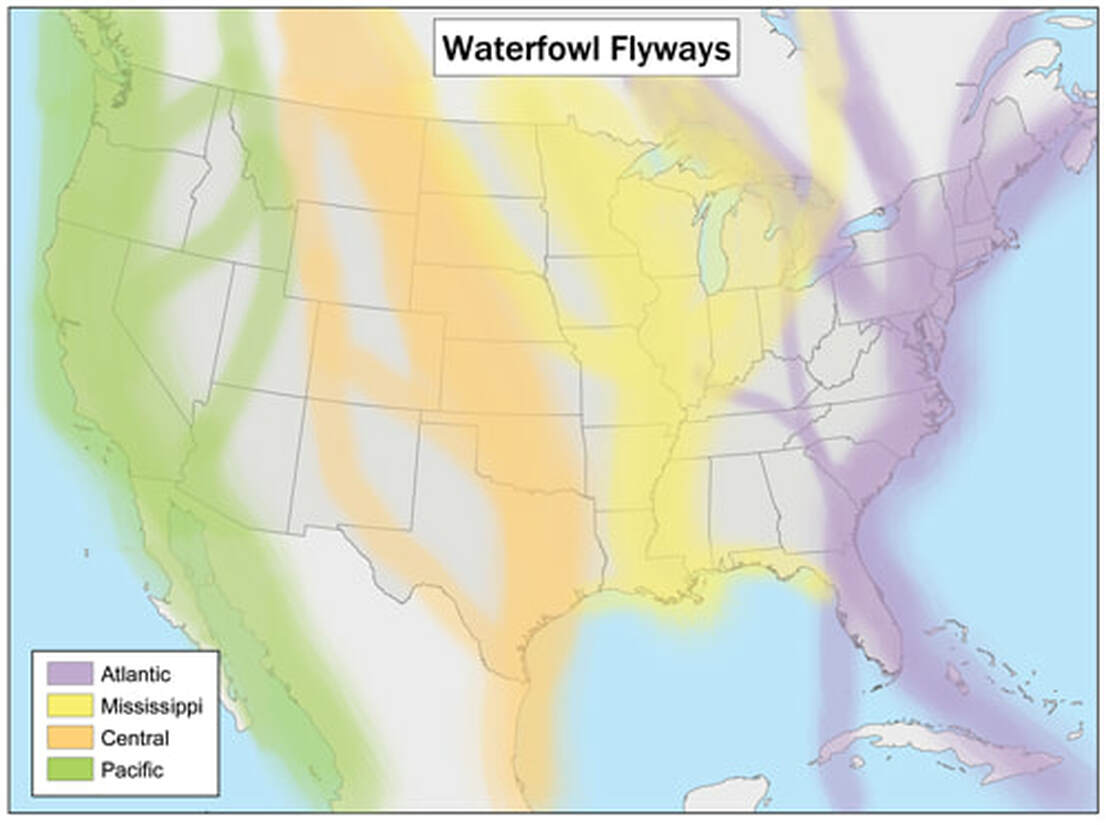

Red knots, although they are small in size, are one of the most intrepid navigators on the planet, traveling the span of the planet and logging over 15,000 each way from the tip of South America to the Canadian Arctic, and back, each year.

The birds typically stay about 12 days and can double their body weight if horse shoe crab eggs are plentiful. Birds that don’t gain enough weight have far lower survival and breeding rates.

Each year between 50% and 80% of the entire species visit Delaware Bay, which spans the Atlantic coast from Delaware to New Jersey, which makes them highly vulnerable to pollution and loss of key resources.

In January 2018, a survey by the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network found that the numbers of Red Knots wintering in Tierra del Fuego, South America had fallen dramatically – to just 9,840 birds. This was a 25% decrease on the number recorded the previous year in January 2017 (13,127).

Bird Life International reports that this decline was likely caused by low ocean temperatures which delayed the Horseshoe Crabs’ journey ashore to breed in May 2017.

When the Red Knots showed up to feed in Delaware Bay, there was little to eat, and the hungry birds didn't survive the journey to the arctic to breed.

The Red Knot was listed as a federally threatened species under the United States Endangered Species Act in the fall of 2014.

Red knots, although they are small in size, are one of the most intrepid navigators on the planet, traveling the span of the planet and logging over 15,000 each way from the tip of South America to the Canadian Arctic, and back, each year.

The birds typically stay about 12 days and can double their body weight if horse shoe crab eggs are plentiful. Birds that don’t gain enough weight have far lower survival and breeding rates.

Each year between 50% and 80% of the entire species visit Delaware Bay, which spans the Atlantic coast from Delaware to New Jersey, which makes them highly vulnerable to pollution and loss of key resources.

In January 2018, a survey by the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network found that the numbers of Red Knots wintering in Tierra del Fuego, South America had fallen dramatically – to just 9,840 birds. This was a 25% decrease on the number recorded the previous year in January 2017 (13,127).

Bird Life International reports that this decline was likely caused by low ocean temperatures which delayed the Horseshoe Crabs’ journey ashore to breed in May 2017.

When the Red Knots showed up to feed in Delaware Bay, there was little to eat, and the hungry birds didn't survive the journey to the arctic to breed.

The Red Knot was listed as a federally threatened species under the United States Endangered Species Act in the fall of 2014.